| [<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->] |

This chapter discusses the basic tools for manipulating files and directories -- tools that are among the most essential on a Linux system.

A file is a collection of data that is stored on disk and that can be manipulated as a single unit by its name.

A directory is a file that acts as a folder for other files. A directory can also contain other directories (subdirectories); a directory that contains another directory is called the parent directory of the directory it contains.

A directory tree includes a directory and all of its files, including the contents of all subdirectories. (Each directory is a "branch" in the "tree.") A slash character alone (`/') is the name of the root directory at the base of the directory tree hierarchy; it is the trunk from which all other files or directories branch.

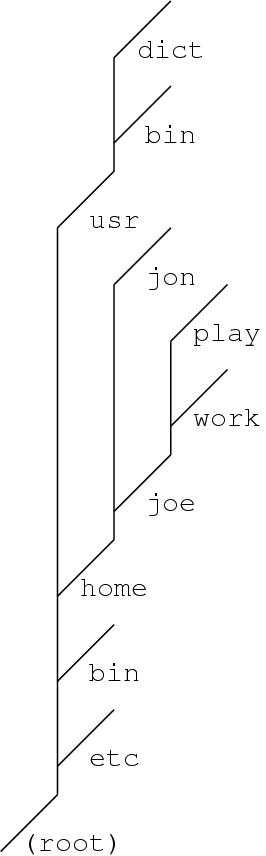

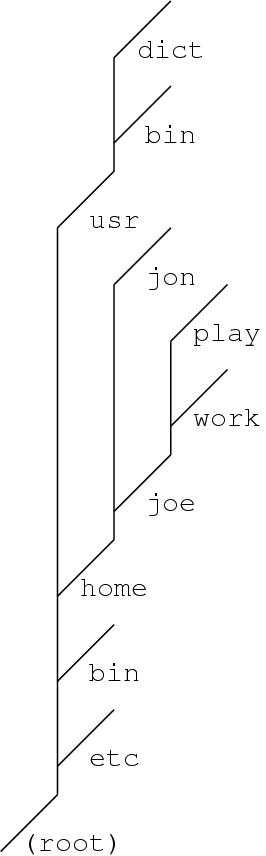

The following image shows an abridged version of the directory hierarchy.

To represent a directory's place in the file hierarchy, specify all of the directories between it and the root directory, using a slash (`/') as the delimiter to separate directories. So the directory `dict' as it appears in the preceding illustration would be represented as `/usr/dict'.

Each user has a branch in the `/home' directory for their own files, called their home directory. The hierarchy in the previous illustration has two home directories: `joe' and `jon', both subdirectories of `/home'.

When you are in a shell, you are always in a directory on the system, and that directory is called the current working directory. When you first log in to the system, your home directory is the current working directory.

Whenever specifying a file name as an argument to a tool or application, you can give the slash-delimited path name relative to the current working directory. For example, if `/home/joe' is the current working directory, you can use work to specify the directory `/home/joe/work', and work/schedule to specify `schedule', a file in the `/home/joe/work' directory.

Every directory has two special files whose names consist of one and two periods: `..' refers to the parent of the current working directory, and `.' refers to the current working directory itself. If the current working directory is `/home/joe', you can use `.' to specify `/home/joe' and `..' to specify `/home'. Furthermore, you can specify the `/home/jon' directory as ../jon.

Another way to specify a file name is to specify a slash-delimited list of all of the directory branches from the root directory (`/') down to the file to specify. This unique, specific path from the root directory to a file is called the file's full path name. (When referring to a file that is not a directory, this is sometimes called the absolute file name).

You can specify any file or directory on the system by giving its full

path name. A file can have the same name as other files in different

directories on the system, but no two files or directories can share a

full path name. For example, user joe can have a file

`schedule' in his `/home/joe/work' directory and a file

`schedule' in his `/home/joe/play' directory. While both files

have the same name (`schedule'), they are contained in different

directories, and each has a unique full path

name---`/home/joe/work/schedule' and

`/home/joe/play/schedule'.

However, you don't have to type the full path name of a tool or application in order to start it. The shell keeps a list of directories, called the path, where it searches for programs. If a program is "in your path," or in one of these directories, you can run it simply by typing its name.

By default, the path includes `/bin' and `/usr/bin'. For

example, the who command is in the `/usr/bin' directory, so

its full path name is /usr/bin/who. Since the `/usr/bin'

directory is in the path, you can type who to run

/usr/bin/who, no matter what the current working directory is.

The following table describes some of the standard directories on Linux systems.

| DIRECTORY | DESCRIPTION |

/ |

The ancestor of all directories on the system; all other directories are subdirectories of this directory, either directly or through other subdirectories. |

/bin |

Essential tools and other programs (or binaries). |

/dev |

Files representing the system's various hardware devices. For example, you use the file `/dev/cdrom' to access the CD-ROM drive. |

/etc |

Miscellaneous system configuration files, startup files, etcetera. |

/home |

The home directories for all of the system's users. |

/lib |

Essential system library files used by tools in `/bin'. |

/proc |

Files that give information about current system processes. |

/root |

The superuser's home directory, whose username is

root. (In the past, the home directory for the superuser was

simply `/'; later, `/root' was adopted for this purpose to

reduce clutter in `/'.)

|

/sbin |

Essential system administrator tools, or system binaries. |

/tmp |

Temporary files. |

/usr |

Subdirectories with files related to user tools and applications. |

/usr/X11R6 |

Files relating to the X Window System, including those programs (in `/usr/X11R6/bin') that run only under X. |

/usr/bin |

Tools and applications for users. |

/usr/dict |

Dictionaries and word lists (slowly being outmoded by `/usr/share/dict'). |

/usr/doc |

Miscellaneous system documentation. |

/usr/games |

Games and amusements. |

/usr/info |

Files for the GNU Info hypertext system. |

/usr/lib |

Libraries used by tools in `/usr/bin'. |

/usr/local |

Local files -- files unique to the individual system -- including local documentation (in `/usr/local/doc') and programs (in `/usr/local/bin'). |

/usr/man |

The online manuals, which are read with the man

command (see Reading a Page from the System Manual).

|

/usr/share |

Data for installed applications that is architecture-independent and can be shared between systems. A number of subdirectories with equivalents in `/usr' also appear here, including `/usr/share/doc', `/usr/share/info', and `/usr/share/icons'. |

/usr/src |

Program source code for software compiled on the system. |

/usr/tmp |

Another directory for temporary files. |

/var |

Variable data files, such as spool queues and log files. |

File names can consist of upper- and lowercase letters, numbers, periods (`.'), hyphens (`-'), and underscores (`_').(15) File names are also case sensitive---`foo', `Foo' and `FOO' are all different file names. File names are almost always all lowercase letters.

Linux does not force you to use file extensions, but it is convenient and useful to give files proper extensions, since they will help you to identify file types at a glance. You can have files with multiple extensions, such as `long.file.with.many.extensions', and you can have files with none at all, such as `myfile'. A JPEG image file, for example, does not have to have a `.jpg' or `.jpeg' extension, and program files do not need a special extension to make them work.

The file name before any file extensions is called the base file name. For example, the base file name of `house.jpeg' is `house'.

Some commonly used file extensions are shown in the following table, including extensions for text and graphics files. (See Converting Images between Formats, for more extensions used with image files, and see Playing a Sound File, for extensions used with sound files.)

| EXTENSION | DESCRIPTION |

.txt or .text |

Plain, unformatted text. |

.tex |

Text formatted in the TeX or LaTeX formatting language. |

.ltx or .latex |

Text formatted in the LaTeX formatting language (neither are as common as just using `.tex'). |

.gz |

A compressed file. |

.sgml |

SGML ("Standardized General Markup Language") format. |

.html |

HTML ("Hypertext Markup Language") format. |

.xml |

XML ("Extended Markup Language") format. |

You may sometimes want to create a new, empty file as a kind of

"placeholder." To do so, give the name that you want to use for the

file as an argument to touch.

$ touch a_fresh_start [RET]

$ touch work/completed/another_empty_file [RET]

This tool "touches" the files you give as arguments. If a file does not exist, it creates it; if the file already exists, it changes the modification timestamp on the file to the current date and time, just as if you had used the file.

NOTE: Often, you make a file when you edit it, such as when in a text or image or sound editor; in that case, you don't need to make the file first.

Use mkdir ("make directory") to make a new directory, giving

the path name of the new directory as an argument. Directory names

follow the same conventions as used with other files -- that is, no

spaces, slashes, or other unusual characters are recommended.

$ mkdir work [RET]

$ mkdir /tmp/work [RET]

Use mkdir with the `-p' option to make a subdirectory and

any of its parents that do not already exist. This is useful when you

want to make a fairly complex directory tree from scratch, and don't

want to have to make each directory individually.

$ mkdir -p work/completed/2001 [RET]

This makes a `2001' subdirectory in the directory called `completed', which in turn is in a directory called `work' in the current directory; if the `completed' or the `work' directories do not already exist, they are made as well (if you know that `work' and `completed' both exist, the above command works fine without the `-p' option).

Use cd to change the current working directory; give the

name of the new directory as an argument.

$ cd work [RET]

$ cd .. [RET]

You can also give the full path name of a directory.

$ cd /usr/doc [RET]

This command makes `/usr/doc' the current working directory.

With no arguments, cd makes your home directory the current

working directory.

$ cd [RET]

To return to the last directory you were in, use cd and give

`-' as the directory name. For example, if you are in the

`/home/mrs/work/samples' directory, and you use cd to change

to some other directory, then at any point while you are in this other

directory you can type cd - to return the current working

directory to `/home/mrs/work/samples'.

$ cd - [RET]

To determine what the current working directory is, use pwd

("print working directory"), which lists the full path name of the

current working directory.

$ pwd [RET] /home/mrs $

In this example, pwd output the text `/home/mrs', indicating

that the current working directory is `/home/mrs'.

Debian: `mc' Debian: `mozilla' WWW: http://www.gnome.org/mc/ WWW: http://www.mozilla.org/

Use ls to list the contents of a directory. It takes as

arguments the names of the directories to list. With no arguments,

ls lists the contents of the current working directory.

$ ls [RET] apple cherry orange $

In this example, the current working directory contains three files: `apple', `cherry', and `orange'.

$ ls work [RET]

$ ls /usr/doc [RET]

You cannot discern file types from the default listing; directories and

executables are indistinguishable from all other files. Using the

`-F' option, however, tells ls to place a `/' character

after the names of subdirectories and a `*' character after the

names of executable files.

$ ls -F [RET] repeat* test1 test2 words/ $

In this example, the current directory contains an executable file named `repeat', a directory named `words', and some other files named `test1' and `test2'.

Another way to list the contents of directories -- and one I use all the

time, when I'm in X and when I also want to look at image files in those

directories -- is to use Mozilla or some other Web browser as a local

file browser. Use the prefix(16) file:/ to view local files. Alone, it opens a

directory listing of the root directory; file:/home/joe opens a

directory listing of user joe's home directory,

file:/usr/local/src opens the local source code directory, and so

on. Directory listings will be rendered in HTML on the fly in almost all

browsers, so you can click on subdirectories to traverse to them, and

click on files to open them in the browser.

Yet another way to list the contents of directories is to use a "file

manager" tool, of which there are at least a few on Linux; the most

popular of these is probably the "Midnight Commander," or mc.

The following subsections describe some commonly used options for

controlling which files ls lists and what information about those

files ls outputs. It is one of the most often used file commands

on Unix-like systems.

Use ls with the `-l' ("long") option to output a more

extensive directory listing -- one that contains each file's size in

bytes, last modification time, file type, and ownership and permissions

(see File Ownership).

$ ls -l /usr/doc/bash [RET] total 72 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 13744 Oct 19 22:57 CHANGES.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1816 Oct 19 22:57 COMPAT.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 16398 Oct 19 22:57 FAQ.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2928 Oct 19 22:57 INTRO.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 4751 Oct 19 22:57 NEWS.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1588 Oct 19 22:57 POSIX.NOTES.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 2718 Oct 19 22:57 README.Debian.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 19596 Oct 19 22:57 changelog.gz -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 1446 Oct 19 22:57 copyright drwxr-xr-x 9 root root 1024 Jul 25 1997 examples $

This command outputs a verbose listing of the files in `/usr/doc/bash'. The first line of output gives the total amount of disk space, in 1024-byte blocks, that the files take up (in this example, 72). Each subsequent line displays several columns of information about one file.

The first column displays the file's type and permissions. The first character in this column specifies the file type; the hyphen (`-') is the default and means that the file is a regular file. Directories are denoted by `d', and symbolic links (see Giving a File More than One Name) are denoted by `l'. The remaining nine characters of the first column show the file permissions (see Controlling Access to Files). The second column lists the number of hard links to the file. The third and fourth columns give the names of the user and group that the file belongs to. The fifth column gives the size of the file in bytes, the sixth column gives the date and time of last modification, and the last column gives the file name.

Use the `-R' option to list a directory recursively, which outputs a listing of that directory and all of its subdirectories.

$ ls -R [RET] play work play: notes work: notes $

In this example, the current working directory contains two subdirectories, `work' and `play', and no other files. Each subdirectory contains a file called `notes'.

$ ls -R / [RET]

This command recursively lists the contents of the root directory, `/', and all of its subdirectories. It is common to combine this with the attribute option, `-l', to output a verbose listing of all the files on the system:

$ ls -lR / [RET]

NOTE: You can't list the contents of some directories on the system if you don't have permission to do so (see Controlling Access to Files).

Use the `-t' option with ls to sort a directory listing so

that the newest files are listed first.

$ ls -t /usr/tmp [RET]

By default, ls does not output files that begin with a period

character (`.'). To reduce clutter, many applications "hide"

configuration files in your home directory by giving them names that

begin with a period; these are called dot files, or sometimes

"hidden" files. As mentioned earlier, every directory has two special

dot files: `..', the parent directory, and `.', the directory

itself.

To list all contents of a directory, including these dot files, use the `-a' option.

$ ls -a [RET]

Use the `-A' option to list almost all files in the directory: it lists all files, including dot files, with the exception of `..' and `.'.

$ ls -A [RET]

Use ls with the `--color' option to list the directory

contents in color; files appear in different colors depending on their

content. Some of the default color settings include displaying

directory names in blue, text files in white, executable files in green,

and links in turquoise.

NOTE: It's common practice to create a command alias that substitutes `ls --color' for `ls', so that typing just ls outputs a color listing. To learn more about making aliases, see Making a Command Alias.

Debian: `tree' WWW: ftp://mama.indstate.edu/linux/tree/

Use tree to output an ASCII text tree graph of a given directory

tree.

$ tree [RET] . |-- projects | |-- current | `-- old | |-- 1 | `-- 2 `-- trip `-- schedule.txt 4 directories, 3 files $

In the preceding example, a tree graph is drawn showing the current directory, which contains the two directories `projects' and `trip'; the `projects' directory in turn contains the directories `current' and `old'.

To output a tree graph of a specific directory tree, give the name of that directory tree as an argument.

$ tree ~ [RET]

To output a graph of a directory tree containing directory names only, use the `-d' option. This is useful for outputting a directory tree of the entire system, or for getting a picture of a particular directory tree.

$ tree -d / > tree [RET]

$ tree -d /usr/local |less [RET]

NOTE: Another tool for outputting directory trees is described in Listing a File's Disk Usage.

The ls tool has many options to control the files listed

and the information given for each file; the following table

describes some of them. (The options are case sensitive.)

| OPTION | DESCRIPTION |

--color |

Colorize the names of files depending on their type. |

-R |

Produce a recursive listing. |

-a |

List all files in a directory, including hidden, or "dot," files. |

-d |

List directories by name instead of listing their contents. |

-f |

Do not sort directory contents; list them in the order they are written on the disk. |

-l |

Produce a verbose listing. |

-r |

Sort directory contents in reverse order. |

-s |

Output the size -- as an integer in 1K blocks -- of each file to the left of the file name. |

-t |

Sort output by timestamp instead of alphabetically, so the newest files are listed first. |

Use cp ("copy") to copy files. It takes two arguments: the

source file, which is the existing file to copy, and the target file,

which is the file name for the new copy. cp then makes an

identical copy of the source file, giving it the specified target

name. If a file with the target name already exists, cp

overwrites it. It does not alter the source file.

$ cp my-copy neighbor-copy [RET]

This command creates a new file called `neighbor-copy' that is identical to `my-copy' in every respect except for its name, owner, group, and timestamp -- the new file has a timestamp that shows the time when it was copied. The file `my-copy' is not altered.

Use the `-p' ("preserve") option to preserve all attributes of the original file, including its timestamp, owner, group, and permissions.

$ cp -p my-copy neighbor-copy [RET]

This command copies the file `my-copy' to a new file called `neighbor-copy' that is identical to `my-copy' in every respect except for its name.

To copy a directory along with the files and subdirectories it contains,

use the -R option -- it makes a recursive copy of the

specified directory and its entire contents.

$ cp -R public_html private_html [RET]

The `-R' option does not copy files that are symbolic links (see Giving a File More than One Name), and it does not retain all original permissions. To recursively copy a directory including links, and retain all of its permissions, use the `-a' ("archive") option. This is useful for making a backup copy of a large directory tree.

$ cp -a public_html private_html [RET]

Use the mv ("move") tool to move, or rename, a file or

directory to a different location. It takes two arguments: the name of

the file or directory to move followed by the path name to move it

to. If you move a file to a directory that contains a file of the same

name, the file is overwritten.

$ mv notes ../play [RET]

This command moves the file `notes' in the current directory to `play', a subdirectory of the current working directory's parent. If a file `notes' already exists in `play', that file is overwritten. If the subdirectory `play' does not exist, this command moves `notes' to its parent directory and renames it `play'.

To move a file or directory that is not in the current directory, give its full path name as an argument.

$ mv /usr/tmp/notes . [RET]

This command moves the file `/usr/tmp/notes' to the current working directory.

To move a directory, give the path name of the directory you want to move and the path name to move it to as arguments.

$ mv work play [RET]

This command moves the directory `work' in the current directory to

the directory `play'. If the directory `play' already exists,

mv puts `work' inside `play'---it does not overwrite

directories.

Renaming a file is the same as moving it; just specify as arguments the file to rename followed by the new file name.

$ mv notes notes.old [RET]

WWW: http://eternity.2y.net/chcase

To change the uppercase letters in a file name to lowercase (or vice

versa), use chcase. It takes as arguments the files whose names

it should change.

$ chcase * [RET]

Use the `-u' option to change file names to all uppercase letters.

$ chcase -u ~/tmp/*.dos [RET]

By default, chcase does not rename directories; use the `-d'

option to rename directories as well as other files. The `-r'

option recursively descends into any subdirectories and renames those

files, too.

$ chcase -d * [RET]

$ chcase -d -r -u * [RET]

$ chcase -r * [RET]

WWW: http://eternity.2y.net/chcase

To give a different file name extension to a group of files that share

the same file name extension, use chcase with the `-x'

option for specifying a Perl expression; give the patterns to match the

source and target files as a quoted argument.

For example, you can rename all file names ending in `.htm' to end in `.html' by giving `s/htm/html/' as the expression to use.

$ chcase -x 's/htm/html/' '*.htm' [RET]

By default, chcase will not overwrite files; so if you want to

rename `index.htm' to `index.html', and both files already

exist in the current directory, the above example will do nothing. Use

the `-o' option to specify that existing files may be

overwritten.

$ chcase -o -x 's/htm/html/' '*.htm' [RET]

NOTE: Renaming multiple files at once is a common request.

Use rm ("remove") to delete a file and remove it from the

system. Give the name of the file to remove as an argument.

$ rm notes [RET]

To remove a directory and all of the files and subdirectories it contains, use the `-R' ("recursive") option.

$ rm -R waste [RET]

To remove an empty directory, use rmdir; it removes the empty

directories you specify. If you specify a directory that contains files

or subdirectories, rmdir reports an error.

$ rmdir empty [RET]

Files with strange characters in their names (like spaces, control characters, beginning hyphens, and so on) pose a problem when you want to remove them. There are a few solutions to this problem.

One way is to use tab completion to complete the name of the file (see Letting the Shell Complete What You Type). This works when the name of the file you want to remove has enough characters to uniquely identify it so that completion can work.

$ rm No[TAB] Way [RET]

In the above example, after [TAB] was typed, the shell filled in the rest of the file name (` Way').

When a file name begins with a control character or other strange character, specify the file name with a file name pattern that uniquely identifies it (see Specifying File Names with Patterns, for tips on building file name patterns). Use the `-i' option to verify the deletion.

$ rm -i ?cat [RET] rm: remove `^Acat'? y [RET] $

In the above example, the expansion pattern `?cat' matches the file

`^Acat' and no other files in the directory. The `-i' option

was used because, in some cases, no unique pattern can be made for a

file -- for example, if this directory also contained a file called

`1cat', the above rm command would also attempt to remove

it; with the `-i' option, you can answer n to it.

These first two methods will not work with files that begin with a

hyphen character, because rm will interpret such a file name as

an option; to remove such a file, use the `--' option -- it

specifies that what follows are arguments and not options.

$ rm -- -cat [RET]

WWW: ftp://ftp.wg.omron.co.jp/pub/unix-faq/docs WWW: http://dsl.org/comp/tinyutils/

Once a file is removed, it is permanently deleted and there is no

command you can use to restore it; you cannot "undelete" it. (Although

if you can unmount the filesystem that contained the file immediately

after you deleted the file, a wizard might be able to help reconstruct

the lost file by using grep to search the filesystem device

file.)

A safer way to remove files is to use del, which is simply an

alias to rm with the `-i' option. This specifies for

rm to run in interactive mode and confirm the deletion of

each file. It may be good practice to get in the habit of using

del all the time, so that you don't make an accidental slip and

rm an important file.

NOTE: Question 3.6 in the Unix FAQ (see

`/usr/doc/FAQ/unix-faq-part3') discusses this issue, and gives a

shell script called can that you can use in place of

rm---it puts files in a "trashcan" directory instead of

removing them; you then periodically empty out the trashcan with

rm.

Links are special files that point to other files; when you act on a file that is a link, you act on the file it points to. There are two kinds of links: hard links and symbolic links. A hard link is another name for an existing file; there is no difference between the link and the original file. So if you make a hard link from file `foo' to file `bar', and then remove file `bar', file `foo' is also removed. Each file has at least one hard link, which is the original file name itself. Directories always have at least two hard links -- the directory name itself (which appears in its parent directory) and the special file `.' inside the directory. Likewise, when you make a new subdirectory, the parent directory gains a new hard link for the special file `..' inside the new subdirectory.

A symbolic link (sometimes called a "symlink" or "soft link") passes most operations -- such as reading and writing -- to the file it points to, just as a hard link does. However, if you remove a symlink, you remove only the symlink itself, and not the original file.

Use ln ("link") to make links between files. Give as arguments

the name of the source file to link from and the name of the new file to

link to. By default, ln makes hard links.

$ ln seattle emerald-city [RET]

This command makes a hard link from an existing file, `seattle', to a new file, `emerald-city'. You can read and edit file `emerald-city' just as you would `seattle'; any changes you make to `emerald-city' are also written to `seattle' (and vice versa). If you remove the file `emerald-city', file `seattle' is also removed.

To create a symlink instead of a hard link, use the `-s' option.

$ ln -s seattle emerald-city [RET]

After running this command, you can read and edit `emerald-city'; any changes you make to `emerald-city' will be written to `seattle' (and vice versa). But if you remove the file `emerald-city', the file `seattle' will not be removed.

The shell provides a way to construct patterns, called file name expansions, that specify a group of files. You can use them when specifying file and directory names as arguments to any tool or application.

The following table lists the various file expansion characters and their meaning.

| CHARACTER | DESCRIPTION |

* |

The asterisk matches a series of zero or more characters, and is sometimes called the "wildcard" character. For example, * alone matches all file names, a* matches all file names that consist of an `a' character followed by zero or more characters, and a*b matches all file names that begin with an `a' character and end with a `b' character, with any (or no) characters in between. |

? |

The question mark matches exactly one character. Therefore, ? alone matches all file names with exactly one character, ?? matches all file names with exactly two characters, and a? matches any file name that begins with an `a' character and has exactly one character following it. |

[list] |

Square brackets match one character in list. For example, [ab] matches exactly two file names: `a' and `b'. The pattern c[io] matches `ci' and `co', but no other file names. |

~ |

The tilde character expands to your home directory. For example, if

your username is joe and therefore your home directory is

`/home/joe', then `~' expands to `/home/joe'. You can

follow the tilde with a path to specify a file in your home

directory -- for example, `~/work' expands to

`/home/joe/work'.

|

| CHARACTER | DESCRIPTION |

- |

A hyphen as part of a bracketed list denotes a range of characters to match -- so [a-m] matches any of the lowercase letters from `a' through `m'. To match a literal hyphen character, use it as the first or last character in the list. For example, a[-b]c matches the files `a-c' and `abc'. |

! |

Put an exclamation point at the beginning of a bracketed list to match all characters except those listed. For example, a[!b]c matches all files that begin with an `a' character, end with a `c' character, and have any one character, except a `b' character, in between; it matches `aac', `a-c', `adc', and so on. |

$ ls /usr/bin/*tex* [RET]

$ cp *.txt doc [RET]

$ ls -lt *.txt *.text [RET]

$ mv /usr/tmp/song[0-9].cdda ~/music [RET]

$ rm -- -*out* [RET]

$ cat a??* [RET]

You can view and peruse local files in a Web browser, such as the

text-only browser lynx or the graphical Mozilla browser for X.

The lynx tool is very good for browsing files on the

system -- give the name of the directory to browse, and lynx will

display a listing of available files and directories in that directory.

You can use the cursor keys to browse and press [RET] on a

subdirectory to traverse to that directory; lynx can display

plain text files, compressed text files, and files written in HTML; it's

useful for browsing system documentation in the `/usr/doc' and

`/usr/share/doc' directories, where many software packages come

with help files and manuals written in HTML.

$ lynx /usr/doc [RET]

For more about using lynx, see Reading Text from the Web.

With Mozilla and some other browsers you must precede the full path name

with the `file:/' URN -- so the `/usr/doc' directory would be

`file://usr/doc'. With lynx, just give a local path name as

an argument.

Location window:

file://usr/doc

[<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->]