| [<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->] |

Next to email, the most useful service on the Internet is the World Wide Web (often written "WWW" or "Web"). It is a giant network of hypertext documents and services, and it keeps growing by the instant -- anyone with an Internet-connected computer can read anything on the Web, and anyone can publish to the Web. It could well be the world's largest public repository of information.

This chapter describes tools for accessing and using the Web. It also describes tools for writing text files in HTML ("HyperText Markup Language"), the native document format of the Web.

Debian: `mozilla' Debian: `skipstone' WWW: http://www.mozilla.org/ WWW: http://galeon.sourceforge.net/ WWW: http://www.muhri.net/skipstone/

When most people think of browsing or surfing the Web, they think of

doing it graphically -- and the mental image they conjure is usually that

of the famous Netscape Web browser. Most Web sites today make heavy use

of graphic images; furthermore, commercial Web sites are usually

optimized for Netscape-compatible browsers -- many of them not even

accessible with other alternative browsers. That means you'll

want to use this application for browsing this kind of Web site.

The version of Netscape's browser which had been released as free, open source software (see What's Open Source?) in 1998 to much fanfare is called Mozilla.(40) When first released, the Mozilla application was a "developer's only" release, but as of this writing it is finally reaching a state where it is ready for general use.

Once the Mozilla browser has been installed, run it in X either by

typing mozilla in a shell or by selecting it from a menu in the

usual fashion, as dictated by your window manager.

Like most graphical Web browsers, its use is fairly self-explanatory;

type a URL in the Location dialog box to open that URL, and

left-click on a link to follow it, replacing the contents of the

browser's main window with the contents of that link. One nice feature

for Emacs fans is that you can use Emacs-style keystrokes for cursor

movement in Mozilla's dialog boxes (see Basic Emacs Editing Keys).

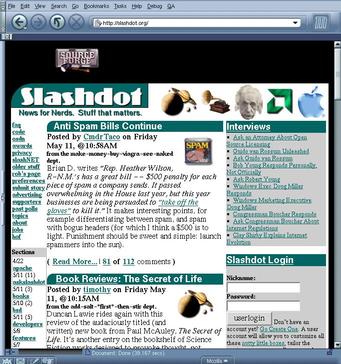

A typical Mozilla window looks like this:

(In this example, the URL http://slashdot.org/ is loaded.)

A criticism of the earlier Netscape Navigator programs is that the browser is a bloated application: it contained its own email client, its own Usenet newsreader, and other functions that are not necessary when one wants to simply browse the Web. Since Mozilla is free software, anyone can take out these excess parts to make a slimmer, faster, smaller application -- and that is what some have done. Two of these projects, Galeon and Skipstone, show some promise; see the above URLs for their home pages.(41)

The following recipes will help you get the most out of using a graphical Web browser in Linux.

NOTE: Mozilla development is moving very rapidly these days, and while Mozilla is continually improving at a fantastic rate, some of these recipes may not work as described with the version you have.

Another way to browse the Web is to use Emacs (see Browsing the Web in Emacs); more alternative browsers are listed in More Web Browsers and Tools.

Debian: `browser-history' WWW: http://www.inria.fr/koala/colas/browser-history/

Use the browser-history tool to maintain a history log of all the

Web sites you visit.

You start it in the background, and each time you visit a URL in a Web browser (as of this writing, works with the Netscape, Arena, and Amaya browsers), it writes the name and URL to its current history log, which you can view at any time.

browser-history every time you start X, put the

following line in your `.xsession' file:

browser-history &

The browser history logs are kept in a hidden directory called `.browser-history' in your home directory. The current history log is always called `history-log.html'; it's an HTML file that you can view in a Web browser.

lynx, type:

$ lynx ~/.browser-history/history-log.html [RET]

Past history logs have the year, month, and week appended to their name, and they are compressed (see Compressed Files). After uncompressing them, you can view them just as you would view the current log (if you are viewing them in Mozilla, you don't even need to uncompress them -- it handles this automagically.)

You can also use zgrep to search through your old browser history

logs. The logs keep the URL and title of each site you visit, so you can

search for either -- then when someone asks, "Remember that good article

about such-and-such?" you can do a zgrep on the files in your

`~/.browser-history' directory to find it.

$ zgrep Confessions ~/.browser-history/history-log-2000* [RET]

This command searches all your logs from the year 2000 for the text `Confessions' in it, and outputs those lines.

NOTE: For more about zgrep, see Matching Lines in Compressed Files.

To open a Web page in Mozilla from a shell script, use the `-remote' option followed by the text `'openURL(URL)'', where URL is the URL to open.

mozilla -remote 'openURL(http://www.drudgereport.com/)'

The following tips make Web browsing with Mozilla easier and more efficient.

Load Images

button. You can also right-click on the broken-image icon of the image

you want to load and select Open this Image.

Open

this Link; the link will open in the current browser window.

Go menu is very large, and

earlier URLs are truncated, you can still visit them by doing this:

left-click one of the lowest entries on the menu, and visit that; then,

left-click on the Home button. This eliminates all the URLs

in the history list that are more recent than the page you'd just

visited, but all of the old pages will be back in the list.

Debian: `imagemagick' WWW: ftp://ftp.wizards.dupont.com/pub/ImageMagick/

If you just want to view an image file from the Web, you don't have to

use a Web browser at all -- instead, you can use display, giving

the URL you want to view as an argument. This is especially nice for

viewing your favorite webcam image, or for viewing images on ftp

sites -- you don't have to log in or type any other commands at all.

$ display ftp://garbo.uwasa.fi/garbo-gifs/garbo01.gif [RET]

NOTE: When viewing the image, you can use all of the image

manipulation commands that display supports, including resizing

and changing the magnification of the image. For more information about

display, see Viewing an Image in X.

Debian: `lynx' WWW: http://lynx.browser.org/

As of this writing, the venerable lynx is still the standard Web

browser for use on Debian systems; it was also one of the first Web

browsers available for general use.(42) It

can't display graphics at all, but it's a good interface for reading

hypertext.

Type lynx to start it -- if a "start page" is defined, it will

load. The start page is defined in `/etc/lynx.cfg', and can be a

URL pointing to a file on the local system or to an address on the Web;

you need superuser privileges to edit this file. On Debian systems, the

start page comes defined as the Debian home page,

http://www.debian.org/ (but you can change this, of course; many

experienced users write their own start page, containing links to

frequently-visited URLs, and save it as a local file in their home

directory tree).

To open a URL, give the URL as an argument.

$ lynx http://lycaeum.org/ [RET]

When in lynx, the following keyboard commands work:

| COMMAND | DESCRIPTION |

[↑] and [↓] |

Move forward and backward through links in the current document. |

[→] or [RET] |

Follow the hyperlink currently selected by the cursor. |

[←] |

Go back to the previously displayed URL. |

[DEL] |

View a history of all URLs visited during this session. |

[PgDn] or [SPC] |

Scroll down to the next page in the current document. |

[PgUp] |

Scroll up to the previous page in the current document. |

= |

Display information about the current document (like all pages in

lynx, type [←] to go back to the previous

document).

|

g |

Go to a URL; lynx will prompt you for the URL to go to. Type

[↑] to insert on this line the last URL that was

visited; once inserted, you can edit it.

|

h |

Display the lynx help files.

|

q |

Quit browsing and exit the program; lynx will ask to verify

this action.

|

lynx.

NOTE: Emacs users might want to use the `-emacskeys'

option when starting lynx; it enables you to use Emacs-style

keystrokes for cursor movement (see Basic Emacs Editing Keys).

To peruse just the text of an article that's on the Web, output the text

of the URL using lynx with the `-dump' option. This dumps

the text of the given URL to the standard output, and you can pipe this

to less for perusal, or use redirection to save it to a file.

$ lynx -dump http://www.sc.edu/fitzgerald/winterd/winter.html | less [RET]

It's an old net convention for italicized words to be displayed in an etext inside underscores like `_this_'; use the `-underscore' option to output any italicized text in this manner.

By default, lynx annotates all the hyperlinks and produces a list

of footnoted links at the bottom of the screen. If you don't want them,

add the `-nolist' option and just the "pure text" will be

returned.

$ lynx -dump -nolist -underscore http://www.sc.edu/fitzgerald/winterd/winter.html > winter_dreams [RET]

You can do other things with the pure text, like pipe it to

enscript for setting it in a font for printing.

$ lynx -dump -nolist -underscore http://www.sc.edu/fitzgerald/winterd/winter.html | enscript -B -f "Times-Roman10" [RET]

NOTE: To peruse the plain text of a URL with its HTML tags removed and no formatting done to the text, see Converting HTML to Another Format.

To view a site or Web page that requires registration, use lynx

with the `-auth' option, giving as arguments the username and

password to use for authorization, separating them by a colon (`:')

character.

$ lynx -auth=cypherpunks:cypherpunks http://www.nytimes.com/archive/ [RET]

It's often common to combine this with the options for saving to a file, so that you can retrieve an annotated text copy of a file from a site that normally requires registration.

$ lynx -dump -number_links -auth=cypherpunks:cypherpunks http://www.nytimes.com/archive/ > mynews [RET]

NOTE: The username and password argument you give on the command line will be recorded in your shell history log (see Command History), and it will be visible to other users on the system should they look to see what processes you're running (see Listing All of a User's Processes).

The following table describes some of the command-line options

lynx takes.

| OPTION | DESCRIPTION |

-anonymous |

Use the "anonymous ftp" account when retrieving ftp URLs. |

-auth=user:pass |

Use a username of user and password of pass for protected documents. |

-cache=integer |

Keep integer documents in memory. |

-case |

Make searches case-sensitive. |

-dump |

Dump the text contents of the URL to the standard output, and then exit. |

-emacskeys |

Enable Emacs-style key bindings for movement. |

-force_html |

Forces rendering of HTML when the URL does not have a `.html' file name extension. |

-help |

Output a help message showing all available options, and then exit. |

-localhost |

Disable URLs that point to remote hosts -- useful for using

lynx to read HTML- or text-format documentation in

`/usr/doc' and other local documents while not connected to the

Internet.

|

-nolist |

Disable the annotated link list in dumps. |

-number_links |

Number links both in dumps and normal browse mode. |

-partial |

Display partial pages while downloading. |

-pauth=user:pass |

Use a username of user and password of pass for protected proxy servers. |

-underscore |

Output italicized text like _this_ in dumps. |

-use_mouse |

Use mouse in an xterm.

|

-version |

Output lynx version and exit.

|

-vikeys |

Enable vi-style key bindings for movement.

|

-width=integer |

Format dumps to a width of integer columns (default 80). |

Debian: `w3-el-e20' WWW: ftp://ftp.cs.indiana.edu/pub/elisp/w3/

Bill Perry's Emacs/W3, as its name implies, is a Web browser for Emacs

(giving you, as Bill says, one less reason to leave the editor). Its

features are many -- just about the only things it lacks that you may

miss are SSL support (although this is coming) and JavaScript and Java

support (well, you may not miss it, but it will make those sites

that require their use a bit hard to use). It can handle frames, tables,

stylesheets, and many other HTML features.

W3 in Emacs, type:

M-x w3 [RET]

To open a URL in a new buffer, type C-o and, in the minibuffer, give the URL to open (leaving this blank visits the Emacs/W3 home page). Middle-click a link to follow it, opening the URL in a new buffer.

C-o http://gnuscape.org/ [RET]

C-o [RET]

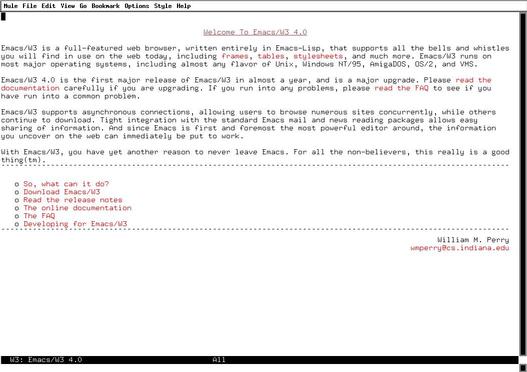

The preceding example opens the Emacs/W3 home page in a buffer of its own:

The following table describes some of the various special W3 commands.

| COMMAND | DESCRIPTION |

[RET] |

Follow the link at point. |

[SPC] |

Scroll down in the current buffer. |

[BKSP] |

Scroll up in the current buffer. |

M-[TAB] |

Insert the URL of the current document into another buffer. |

M-s |

Save a document to the local disk (you can choose HTML Source, Formatted Text, LaTeX Source, or Binary). |

C-o |

Open a URL. |

B |

Move backward in the history stack of visited URLs. |

F |

Move forward in the history stack of visited URLs. |

i |

View information about the document in current buffer (opens in new buffer called `Document Information'). |

I |

View information about the link at point in current buffer (opens in new buffer called `Document Information'). |

k |

Put the URL of the document in the current buffer in the kill ring, and make it the X selection (useful for copying and pasting the URL into another buffer or to another application; see Selecting Text). |

K |

Put the URL of the link at point in the kill ring and make it the X selection (useful for copying and pasting the URL into another buffer or to another application; see Selecting Text). |

l |

Move to the last visited buffer. |

o |

Open a local file. |

q |

Quit W3 mode, kill the current buffer, and go to the last visited buffer. |

r |

Reload the current document. |

s |

View HTML source of the document in the current buffer (opens in new buffer with the URL as its name). |

S |

View HTML source of the link at point in the current buffer (opens in new buffer with the URL as its name). |

v |

Show the URL of the current document (URL is shown in the minibuffer). |

V |

Show URL of the link under point in the current buffer (URL is shown in the minibuffer). |

Debian: `wget' WWW: http://www.wget.org/

Use wget, "Web get," to download files from the World Wide

Web. It can retrieve files from URLs that begin with either `http'

or `ftp'. It keeps the file's original timestamp, it's smaller and

faster to use than a browser, and it shows a visual display of the

download progress.

The following subsections contain recipes for using wget to

retrieve information from the Web. See Info file `wget.info', node `Examples',

for more examples of things you can do with wget.

NOTE: To retrieve an HTML file from the Web and save it as

formatted text, use lynx instead -- see Perusing Text from the Web.

To download a single file from the Web, give the URL of the file as an

argument to wget.

$ wget ftp://ftp.neuron.net/pub/spiral/septembr.mp3 [RET]

This command reads a given URL, writing its contents to a file with the same name as the original, `septembr.mp3', in the current working directory.

If you interrupt a download before it's finished, the contents of the

file you were retrieving will contain only the portion of the file

wget retrieved until it was interrupted. Use wget with the

`-c' option to resume the download from the point it left off.

$ wget -c ftp://ftp.neuron.net/pub/spiral/septembr.mp3 [RET]

NOTE: In order for the `-c' option to have the desired

effect, you should run wget from the same directory as it was run

previously, where that partially-retrieved file should still exist.

To archive a single Web site, use the `-m' ("mirror") option, which saves files with the exact timestamp of the original, if possible, and sets the "recursive retrieval" option to download everything. To specify the number of retries to use when an error occurs in retrieval, use the `-t' option with a numeric argument---`-t3' is usually good for safely retrieving across the net; use `-t0' to specify an infinite number of retries, good for when a network connection is really bad but you really want to archive something, regardless of how long it takes. Finally, use the `-o' with a file name as an argument to write a progress log to the file -- examining it can be useful in the event that something goes wrong during the archiving; once the archival process is complete and you've determined that it was successful, you can delete the log file.

$ wget -m -t3 http://www.bloofga.org/ -o mirror.log [RET]

This command makes an archive of the Web site at `www.bloofga.org' in a subdirectory called `www.bloofga.org' in the current directory. Log messages are written to a file in the current directory called `mirror.log'.

To continue an archive that you've left off, use the `-nc' ("no clobber") option; it doesn't retrieve files that have already been downloaded. For this option to work the way you want it to, be sure that you are in the same directory that you were in when you originally began archiving the site.

$ wget -nc -m -t3 http://www.bloofga.org/ -o mirror.log [RET]

To archive only part of a Web site -- such as, say, a user's home page -- use the `-I' option followed by a list of the absolute path names of the directories to archive; all other directories on the site are ignored.

$ wget -m -t3 -I /~mbt http://dougal.bris.ac.uk/~mbt/ -o uk.log [RET]

This command archives all files on the http://dougal.bris.ac.uk/~mbt/ Web site whose directory names begin with `/~mbt'.

To only get files in a given directory, use the `-r' and `-l1' options (the `-l' option specifies the number of levels to descend from the given level). To only download files in a given directory, combine these options with the `--no-parent' option, which specifies not to ascend to the parent directory.

Use the `-A' option to specify the exact file name extensions to accept -- for example, use `-A txt,text,tex' to only download files whose names end with `.txt', `.text', and `.tex' extensions. The `-R' option works similarly, but specifies the file extensions to reject and not download.

$ wget -m -r -l1 --no-parent -A.gz http://monash.edu.au/~rjh/indiepop-l/download/ [RET]

All Web servers output special headers at the beginning of page requests, but you normally don't see them when you retrieve a URL with a Web browser. These headers contain information such as the current system date of the Web server host and the name and version of the Web server and operating system software.

Use the `-S' option with wget to output these headers when

retrieving files; headers are output to standard output, or to the

log file, if used.

$ wget -S http://slashdot.org/ [RET]

This command writes the server response headers to standard output and saves the contents of http://slashdot.org/ to a file in the current directory whose name is the same as the original file.

Debian: `bluefish' WWW: http://bluefish.openoffice.nl/

Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) is the markup language of the Web; HTML

files are just plain text files written in this markup language. You

can write HTML files in any text editor; then, open the file in a Web

browser to see the HTML markup rendered in its resulting hypertext

appearance.

Many people swear by Bluefish, a full-featured, user-friendly HTML editor for X.

Emacs (see Emacs) has a major mode to facilitate the editing of HTML files; to start this mode in a buffer, type:

M-x html-mode [RET]

The features of HTML mode include the insertion of "skeleton" constructs.

The help text for the HTML mode function includes a very short HTML authoring tutorial -- view the documentation on this function to display the tutorial.

C-h f html-mode [RET]

NOTE: When you're editing an HTML file in an Emacs buffer, you can open the same file in a Web browser in another window -- Web browsers only read and don't write the HTML files they open, so you can view the rendered document in the browser as you create it in Emacs. When you make and save a change in the Emacs buffer, reload the file in the browser to see your changes take effect immediately.

Debian: `imgsizer' WWW: http://www.tuxedo.org/~esr/software.html#imgsizer

For usability, HTML image source tags should have `HEIGHT' and

`WIDTH' parameters, which specify the dimensions of the image the

tag describes. By specifying these parameters in all the image tags on a

page, the text in that page will display in the browser window

before the images are loaded. Without them, the browser must load

all images before any of the text on the page is displayed.

Use imgsizer to automatically determine the proper values and

insert them into an HTML file. Give the name of the HTML file to fix as

an argument.

$ imgsizer index.html [RET]

Debian: `unhtml' Debian: `html2ps' WWW: http://dragon.acadiau.ca/~013639s/ WWW: http://www.tdb.uu.se/~jan/html2ps.html

There are several ways to convert HTML files to other formats. You can

convert the HTML to plain text for reading, processing, or conversion to

still other formats; you can also convert the HTML to PostScript, which

you can view, print, or also convert to other formats, such as PDF.

To simply remove the HTML formatting from text, use unhtml. It

reads from the standard input (or a specified file name), and it writes

its output to standard output.

$ unhtml index.html | less [RET]

$ unhtml index.html > index.txt [RET]

When you remove the HTML tags from a file with unhtml, no further

formatting is done to the text. Furthermore, it only works on files, and

not on URLs themselves.

Use lynx to save an HTML file or a URL as a formatted text

file, so that the resultant text looks like the original HTML when

viewed in lynx. It can also preserve italics and hyperlink

information in the original HTML. See Perusing Text from the Web.

One thing you can do with this lynx output is pipe it to tools

for spacing text, and then send that to enscript for setting in a

font. This is useful for printing a Web page in typescript

"manuscript" form, with images and graphics removed and text set

double-spaced in a Courier font.

$ lynx -dump -underscore -nolist http://example.com/essay/ | pr -d | enscript -B [RET]

NOTE: In some cases, you might want to edit the file before you

print it, such as when a Web page contains text navigation bars or other

text that you'd want to remove before you turn it into a manuscript. In

such a case, you'd pipe the lynx output to a file, edit the file,

and then use pr on the file and pipe that output to

enscript for printing.

Finally, you can use html2ps to convert an HTML file to

PostScript; this is useful when you want to print a Web page with all

its graphics and images, or when you want to convert all or part of a

Web site into PDF. Give the URLs or file names of the HTML files to

convert as options. Use the `-u' option to underline the anchor

text of hypertext links, and specify a file name to write to as an

argument to the `-o' option. The defaults are to not underline

links, and to write to the standard output.

$ html2ps http://example.com/essay/ | lpr [RET]

$ html2ps -u -o submission.ps http://example.com/essay/ [RET]

Debian: `weblint' WWW: http://www.weblint.org/

Use weblint to validate the basic structure and syntax of an HTML

file. Give the name of the file to be checked as an argument, and

weblint outputs any complaints it has with the file to standard

output, such as whether or not IMG elements are missing ALT

descriptions, or whether nested elements overlap.

$ weblint index.html [RET]

Surprisingly, there are not nearly as many Web browsers for Linux as there are text editors -- or even text viewers. This remains true for any operating system, and I have often pondered why this is; perhaps "browsing the Web," a fairly recent activity in itself, may soon be obsoleted by Web readers and other tools. In any event, the following lists other browsers that are currently available for Linux systems.

| WEB BROWSER | DESCRIPTION |

amaya |

Developed by the World Wide Web Consortium; both a graphical Web

browser and a WYSIWYG editor for writing HTML.

Debian: `amaya' WWW: http://www.w3.org/amaya/ |

arena |

Developed by the World Wide Web Consortium; a very compact, HTML

3.0-compliant Web browser for X.

Debian: `arena' WWW: http://www.w3.org/arena/ |

dillo |

A very fast, small graphical Web browser.

Debian: `dillo' WWW: http://dillo.sourceforge.net/ |

express |

A small browser that works in X with GNOME installed.

Debian: `express' WWW: http://www.ca.us.vergenet.net/~conrad/express/ |

links |

A relatively new text-only browser.

WWW: http://artax.karlin.mff.cuni.cz/~mikulas/links/ |

gzilla |

A graphical browser for X, currently in an early stage of development.

Debian: `gzilla' WWW: http://www.levien.com/gzilla/ |

w3m |

Another new text-only browser whose features include table support

and an interesting free-form cursor control; some people swear by this

one.

Debian: `w3m' WWW: http://ei5nazha.yz.yamagata-u.ac.jp/ |

[<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->]