| [<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->] |

This chapter concerns those concepts and commands that every Linux user knows -- how to start and stop the system, log in and out from it, change your password, see what is happening on the system, and use the system help facilities. Mastery of these basic concepts is essential for using Linux with any degree of success.

Some of these recipes make reference to files and directories; these concepts are explained in Files and Directories.

These recipes show how to start and stop power to the system -- how to turn it on and turn it off. It's more than just pressing the button on the case; in particular, there is a right way to turn off the system, and doing it wrong can result in losing some of your work. Fortunately, there isn't any black magic involved, as we soon shall see -- properly shutting down the system is easy!

The first thing you do to begin using the system is start power to it. To power up the system, just turn it on. This is called booting the system.

As the Linux kernel boots there will be many messages on the

screen. After a while, the system will display a login:

prompt. You can now log in. See Logging In to the System.

Some systems are configured to start xdm at boot time

(see Starting X). If your system is configured like

this, instead of the login: prompt described above, you'll see a

graphical screen with a box in the middle containing both login:

and Password: prompts. Type [CTRL]-[ALT]-[F1] to

switch to the first virtual console, where you can log in to the system

in the usual way (see Console Basics).

You can't just flip the power switch when you are done using the computer, because Linux is constantly writing data to disk. (It also keeps data in memory, even when it may have appeared to have written that data to disk.) Simply turning off the power could result in the loss or corruption of some of your work.

The following describes a method of turning off the system that can be done by a normal user; the traditional way of shutting down can only be performed by the superuser, and is described in Shutting Down the System.

To turn off a single user system, first log out of all consoles (discussed in Console Basics). Then, type [CTRL]-[ALT]-[DEL] (press and hold these three keys at once).(10)

The system will print some messages as it shuts down, and when you see the line, `Rebooting...', it's safe to turn the power to machine off.

NOTE: You don't want to wait too long after you see this message; if left untouched, the system will reboot and you'll be back to the beginning!

Linux is a multi-user system, meaning that many users can use one Linux system simultaneously, from different terminals. So to avoid confusion (and to maintain a semblance of privacy), each user's workspace must be kept separate from the others.

Even if a particular Linux system is a stand-alone personal computer with no other terminals physically connected to it, it can be shared by different people at different times, making the separation of user workspace still a valid issue.

This separation is accomplished by giving each individual user an account on the system. You need an account in order to use the system; with an account you are issued an individual workspace to use, and a unique username that identifies you to the system and to other users. It is the name that the system (and those who use it) will then forever know you as; it's a single word, in all lowercase letters.

During the installation process, the system administrator should have

created an account for you. (The system administrator has a special

account whose username is root; this account has total access to

the entire system, so it is often called the superuser.)

Until the mid-1990s it was widely common for usernames to be the first

letter of your first name followed by your entire surname, up to 12

characters total. So for example, user Samuel Clemens would have a

username of sclemens by this convention; this, however, is not a

hard and fast rule, especially on home systems where you may be the only

user. Sometimes, a middle initial may be used ("dkjohnson"), or

sometimes even nicknames or initials are used ("zenboy,"

"xibo"). But whatever username you pick for yourself, make sure

it's one you can live with, and one you can stand being called by both

the system and other users (your username also becomes part of your

email address, as we'll see in Email).

In addition to your username, you should also have a password that you can keep secret so that only you can use your account. Good passwords are strings of text that nobody else is likely to guess (i.e., not obvious words like `secret', or identifying names like `Ruski', if that happens to be your pet cat). A good password is one that is highly memorable to you so that you don't have to write it down, but is complex enough in construction so that anyone else couldn't ever guess it. For example, `t39sAH' might be a fine password for someone whose first date was to see the movie The 39 Steps directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

NOTE: While usernames are always in lowercase, passwords are case sensitive; the passwords `Secret', `secret', and `SECRET' are all considered different.

To begin a session on a Linux system, you need to log in. Do this

by entering your username at the login: prompt on your terminal,

and then entering your password when asked.

The login: prompt appears on the terminal after the system

boots. If your system is configured to start the X Window System at boot

time, you'll be presented with an X login screen instead of the standard

login prompt. If that happens, press [CTRL]-[ALT]-[F1] to

switch to the text login screen; this is explained further in

Console Basics.

A typical login: prompt looks like this:

Debian GNU/Linux 2.2 bardo tty1 bardo login:

Every Linux system has its own name, called the system's hostname;

a Linux system is sometimes called a host, and it identifies

itself with its hostname at the login: prompt. It's important to

name your system -- like a username for a user account, a hostname gives

name to the system you are using (and it becomes especially important

when putting the system on a network). The system administrator usually

names the system when it is being initially configured (the hostname can

always be changed later; its name is kept in the file

`/etc/hostname'). Like usernames, hostnames are one word in all

lowercase letters. People usually give their system a name they like,

such as darkstar or shiva.

In this example, `bardo' is the hostname of this particular Linux system.

The name of the terminal you are connecting from is displayed just after the hostname. In this example, the terminal is `tty1', which means that this is the first terminal on this particular system. (Incidentally, `tty' is short for "teletype," which historically was the kind of terminal hardware that most Unix-based systems used by default.)

To log in to the system, type your username (followed by [RET]) at

the login: prompt, and then type your password when asked (also

followed by [RET]); for security purposes, your password is not

displayed on the screen when you type it.

Debian GNU/Linux 2.2 bardo tty1 bardo login: kurt [RET] Password: empathy [RET] Linux bardo 2.0.30 #1 Tue Jul 29 10:01:26 EDT 1997 i586 unknown Copyright (C) 1993-1998 Software in the Public Interest, and others Most of the programs included with the Debian Linux system are freely redistributable; the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the individual files in /usr/doc/*/copyright Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent permitted by applicable law. Last login: Tue Apr 5 12:03:47 on tty1. No mail. ~ $

Once you've entered your username and password, you are "logged in" to the system. You can then use the system and run commands.

As soon as you log in, the system displays the contents of

`/etc/motd', the "Message of the Day" file. The system then

displays the time and date of your last login, and reports whether or

not you have electronic mail waiting for you (see Email). Finally, the system puts you in a shell---the environment

in which you interact with the system and give it commands. Use of the

default shell on most Linux systems, bash, is discussed

in The Shell.

The dollar sign (`$') displayed to the left of the cursor is called the shell prompt; it means that the system is ready and waiting for input. (You can change this prompt to any text of your liking; to learn how, see Changing the Shell Prompt.) By default, the shell prompt includes the name of the current directory, which it places to the left of the `$' character. The tilde character (`~'), is a shell symbol that denotes the user's home directory -- when you log in, you are in your home directory (these terms are defined in Files and Directories).

To end your session on the system, type logout at the shell

prompt. This command logs you out of the system, and a new login:

prompt appears on your terminal.

$ logout [RET] Debian GNU/Linux 2.2 bardo tty1 bardo login:

What works equally well to typing the logout command is to just

type C-d (hold down [CTRL] and press [D]). You don't even

have to type [RET] afterwards. Many users prefer this quick

shortcut.

Logging out of the system frees the terminal you were using -- and ensures that nobody can access your account from this terminal.

If you are the only person using your system and have just ended a session by logging out, you might want to power down the system. See Turning Off the System, earlier in this chapter.

A Linux terminal is a place to put input and get output from the system, and usually has at least a keyboard and monitor.

When you access a Linux system by the keyboard and monitor that are directly connected to it, you are said to be using the console terminal. (Linux systems can be accessed in other ways, such as through a network or via another terminal connected to a serial line; see Communications).

Linux systems feature virtual consoles, which act as separate console displays that can run separate login sessions, but are accessed from the same physical console terminal. Linux systems are configured to have seven virtual consoles by default. When you are at the console terminal, you can switch between virtual consoles at any time, and you can log in and use the system from several virtual consoles at once.

The following recipes explain the basic things you will need to do with virtual consoles.

To switch to a different virtual console, press [ALT]-[Fn], where n is the number of the console to switch to.

This command switches to the fourth virtual console, denoted by `tty4':

Debian GNU/Linux 2.2 bardo tty4 bardo login:

You can also cycle through the different virtual consoles with the left and right arrow keys. To switch to the next-lowest virtual console (or wrap around to the highest virtual console, if you're at the first virtual console), press [ALT]-[←]. To switch to the next-highest virtual console, press [ALT]-[→].

[ALT]-[←]

This keystroke switches to the third virtual console, `tty3':

Debian GNU/Linux 2.2 bardo tty3 bardo login:

The seventh virtual console is reserved for the X Window System. If X is

installed, this virtual terminal will never show a login: prompt,

but when you are using X, this is where your X session appears. If your

system is configured to start X immediately, this virtual console will

show an X login screen.

You can switch to a virtual console from the X Window System using [CTRL] in conjunction with the usual [ALT] and function keys. This is the only console manipulation keystroke that works in X.

[CTRL]-[ALT]-[F1]

When you are logged in at a virtual console, new lines of text appear at the bottom of the console screen, while older lines of text scroll off the top of the screen.

The amount of text you can scroll back through depends on system memory.

NOTE: This technique is for scrolling through text displayed in your shell session (see The Shell). It does not work for scrolling through text in a tool or application in the console -- in other words, you can't use this technique to scroll through text that is displayed by a tool for perusing text files. To scroll through text in an application, use its own facilities for scrolling, if it has any.

Some keystrokes for manipulating the console display, including those for switching between virtual consoles, are described below. It's a good idea to experiment with these commands until you are comfortable with them, because knowing how to use virtual consoles is basic to using Linux.

| KEYSTROKE | DESCRIPTION |

| [ALT]-[Fn] | Switch to virtual console n, where n is a number from 1 to 7 (the default maximum). |

| [CTRL]-[ALT]-[Fn] | When in X, switch to virtual console n, where n is a number from 1 to 6. |

| [ALT]-[←] | Switch to the next-lowest virtual console. For example, typing this while in virtual console 4 switches to virtual console 3. Pressing this keystroke in the lowest console wraps around to the highest console. |

| [ALT]-[→] | Switch to the next-highest virtual console. For example, typing this while in virtual console 4 switches to virtual console 5. Pressing this keystroke in the highest console wraps around to the lowest console. |

| [SHIFT]-[PgUp] | Scroll back one screen to view previously displayed text. |

| [SHIFT]-[PgDn] | When viewing previously displayed text, scroll forward one screen. |

A tool is a software program that performs a certain

function -- usually a specialized, simple task. For example, the

hostname tool outputs the system's hostname, and the who

tool outputs a listing of the users who are currently logged in. An

application is the name given to larger, usually interactive,

programs for completing broader kinds of tasks -- such as programs for

image editing or word processing.

A tool or application may take any number of options (sometimes called "flags"), which specify a change in its default behavior. It may also take arguments, which specify a file or some other text to operate on. Arguments are usually specified after any options.

A command is the name of a tool or application along with the options and arguments you want to use, if any. Since typing the name of a tool itself is often sufficient to accomplish a desired task, tools alone are often called commands.

Commands are case sensitive; the names of tools and applications are usually in all lowercase letters.

To run (or "execute") a tool or application without giving any options or arguments, type its name at a shell prompt followed by [RET].

hostname tool, type:

$ hostname [RET] bardo $

The hostname of the system in the example is `bardo'.

Options always begin with a hyphen character, `-', which is usually followed by one alphanumeric character. To include an option in a command, follow the name of the tool or application with the option. Always separate the tool name, each option, and each argument with a space character.

Long-style options (sometimes called "GNU-style" options) begin with two hyphen characters (`--') and are usually one English word.

For example, many tools have an option, `--version', to output the version number of the tool. (Many tools also have a `--help' option, which outputs a list of options the tool takes; see Listing the Usage of a Tool.)

hostname tool, type:

$ hostname --version [RET] hostname 2.10 $

This command outputs the text `hostname 2.10', indicating that this

is version 2.10 of the hostname tool.

Sometimes, an option itself may may take an argument. For example,

hostname has an option for specifying a file name to use to read

the hostname from, `-F'; it takes as an argument the name of the

file that hostname should read from.

hostname and specify that the file `host.info' is the

file to read from, type:

$ hostname -F host.info [RET]

To change your password, use the passwd tool. It prompts you for

your current password and a new password to replace it with. For

security purposes, neither the old nor the new password is echoed to the

screen as you type it. To make sure that you type the new password

correctly, passwd prompts you for your new password twice. You

must type it exactly the same way both times, or passwd will not

change your password.

$ passwd [RET] Changing password for kurt Old password: your current password [RET] Enter the new password (minimum of 5, maximum of 8 characters) Please use a combination of upper and lower case letters and numbers. New password: your new password [RET] Re-enter new password: your new password [RET] Password changed. $

NOTE: Passwords can contain uppercase and lowercase letters, the digits 0 through 9, and punctuation marks; they should be between five and eight characters long. See Accounts and Privileges, for suggestions on choosing a good password.

The recipes in this section describe some of the simple commands for finding out who you are currently sharing the system with and what they are doing.

Use whoami to output the username of the user that is logged in

at your terminal. This is not as inutile a command as one might first

think -- if you're at a shared terminal, it's useful to determine whether

or not it is your account that you're messing in, and for those with

multiple accounts on a system, it's useful to see which of them you're

currently logged in with.

$ whoami [RET] kurt $

In this example, the username of the user logged in at this terminal is `kurt'.

Use who to output a list of all the users currently logged in to

the system. It outputs a minimum of three columns, listing the username,

terminal location, and time of login for all users on the system. A

fourth column is displayed if a user is using the X Window System; it

lists the window location of the user's session (see The X Window System).

$ who [RET] murky tty1 Oct 20 20:09 dave tty2 Oct 21 14:37 kurt tty3 Oct 21 15:04 kurt ttyp1 Oct 21 15:04 (:0.0) $

The output in this example shows that the user murky is logged in

on tty1 (the first virtual console on the system), and has been

on since 20:09 on 20 October. The user dave is logged in on

tty2 (the second virtual console), and has been on since 14:37 on

21 October. The user kurt is logged in twice -- on tty3

(the third virtual console), and ttyp1, which is an X session

with a window location of `(:0.0)'.

NOTE: This command is for listing the users on the local system; to list the users connected to a different system on the network, or to see more detailed information that a user may have made public about himself, see Checking Whether a User Is Online.

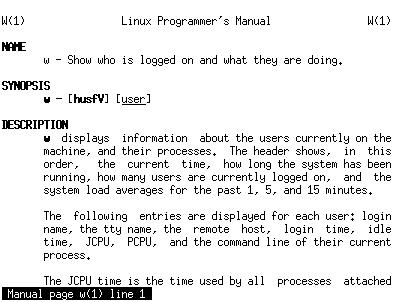

The w tool is similar to who, but it displays more

detail. It outputs a header line that contains information about the

current system status, including the current time, the amount of time

the system has been up and running, and the number of users on the

system. It then outputs a list of users currently logged in to the

system, giving eight columns of information for each. These columns

include username, terminal location, X session (if any), the time of

login, the amount of time the user has been idle, and what command the

user is running. (It also gives two columns showing the amount of time

the system's CPU has spent on all of the user's current jobs ("JCPU")

and foreground process ("PCPU"); processes are discussed in

Listing System Activity, and jobs in Managing Jobs.)

$ w [RET] 5:27pm up 17:53, 4 users, load average: 0.12, 0.06, 0.01 USER TTY FROM LOGIN IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT murky tty1 Oct 20 20:09 17:22m 0.32s 0.32s -bash dave tty2 14:37 13.00s 2:35 0.07s less foo kurt tty3 15:04 1:00m 0.41s 0.09s startx kurt ttyp1 :0.0 15:04 0:00s 21.65s 20.96s emacs $

In this example, the command's output shows that the current system time

is 5:27 p.m., the system has been up for 17 hours and 53 minutes, and

there are four users currently logged in: murky is logged in at

tty1, has been idle for 17 hours and 22 minutes, and is at a

bash shell prompt; dave is logged in at tty2, has

been idle for 13 seconds, and is using less to peruse a file

called `foo' (see Perusing Text); and

kurt is logged in at two terminals---tty3 and

ttyp1, which is an X session. He ran the startx command on

tty3 to start his X session, and within his X session, he is

currently using Emacs.

Use last to find out who has recently used the system, which

terminals they used, and when they logged in and out.

$ last [RET]

To find out when a particular user last logged in to the system, give his username as an argument.

kurt last logged in, type:

$ last kurt [RET]

NOTE: The last tool gets its data from the system file

`/var/log/wtmp'; the last line of output tells how far this file

goes back. Sometimes, the output will go back for several weeks or more.

When you run a command, you are starting a process on the system, which is a program that is currently executing. Every process is given a unique number, called its process ID, or "PID."

Use ps to list processes on the system. Some of the information

it can display about a process includes process ID, name of command

being run, username running the command, and how long the process has

been running. By default, ps outputs 5 columns: process ID, the

name of the terminal from which the process was started, the current

status of the process (including `S' for sleeping, meaning

that it is on hold at the moment, `R' meaning that it is running,

and `Z' meaning that it is a zombie process, or a process

that has already died), the total amount of time the CPU has spent on

the process since the process started, and finally the name of the

command being run.

The following recipes describe popular usage of ps.

Type ps with no arguments to list the processes you have running in your current shell session.

$ ps [RET] PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND 193 1 S 0:01 -bash 204 1 S 0:00 ps $

In this example, ps shows that two processes are running: the

bash and ps commands.

To list all the processes of a specific user, use ps and give the

username to list as an argument to the `-u' option. While you can't

snoop on the actual activities of other users, you can list the commands

they are running at a given moment.

hst has running on the

system, type:

$ ps -u hst [RET]

NOTE: This command is useful for listing all of your own processes, across all terminals and shell sessions; give your own username as an argument.

To list all processes by all users on the system, use the `aux' options.

$ ps aux [RET]

NOTE: There could be a lot of output -- even single-user Linux

systems typically have fifty or more processes running at one time -- so

you may want to pipe the output of this command through less for

perusal (see Perusing Text).

Additionally, use top to show a display of all processes on the

system, sorted by their demand on the system resources. The display is

continually updated with current process information; press Q to

stop the display and exit the program. This tool also displays the

information about system runtime and memory that can be output with the

uptime and free commands.

$ top [RET]

To list processes whose output contains a name or other text to match,

list all processes and pipe the output to grep. This is useful

for when you want to see which users are running a particular program or

command.

$ ps aux | grep sbin [RET]

$ ps aux | grep 13 [RET]

To list the process (if any) which corresponds to a process ID, give that PID as an argument to the `-p' option.

$ ps -p 344 [RET]

Linux systems come with a lot of help facilities, including complete manuals in etext form. In fact, the foremost trouble with Linux documentation isn't that there is not enough of it, but that you have to sift through the mounds of it, trying to find the precise information you're looking for!

I describe the help facilities in the following sections; their relative usefulness for the particular kind of information you're looking for is noted.

If you find that you need more help, don't panic -- other options are available. They're described in If You Need More Help.

When you know what a particular tool or application does, but you

can't remember it's name, use apropos. This tool takes a keyword

as an argument, and it outputs a list of installed software whose

one-line descriptions contain that keyword. This is also useful for

finding software on your system related to, say, "audio" or "sound"

or "sort" or some other such general concept.

$ apropos consoles [RET] console (4) - console terminal and virtual consoles gpm (1) - a cut and paste utility and mouse server for virtual consoles $

NOTE: The apropos tool only finds exact matches, so a

search for the keyword `console' might not list the programs that a

search for the keyword `consoles' would yield, and vice versa.

Another way to find tools by keyword is to search the system manual

pages (see Reading a Page from the System Manual). To do

this, use man and give the text to search for as an argument to

the `-k' option. This searches the short descriptions and manual

page names for the given text, and outputs a list of those tools that

match in the same format as the apropos tool.

$ man -k consoles [RET]

On Debian systems, yet another way to find installed software by keyword

is to use dpkg, the Debian package tool. Use the `-l' option

to list all of the installed packages, which are each output on a line

of their own with their package name and a brief description.

You can output a list of packages that match a keyword by piping the

output to grep. Use the `-i' option with grep to

match keywords regardless of case (grep is discussed in

Searching Text).

Additionally, you can directly peruse the file `/var/lib/dpkg/available'; it lists all available packages and gives a description of them.

$ dpkg -l [RET]

$ dpkg -l | grep -i edit [RET]

$ less /var/lib/dpkg/available [RET]

Use whatis to list a one-line description of a program. Give the

name of the tool or application to list as an argument.

who tool, type:

$ whatis who [RET]

NOTE: The whatis tool gets its descriptions from the

manual page of a given program; manual pages are described later

in this section, in Reading a Page from the System Manual.

Many tools have a long-style option, `--help', that outputs usage information about the tool, including the options and arguments the tool takes.

whoami, type:

$ whoami --help [RET] Usage: whoami [OPTION]... Print the user name associated with the current effective user id. Same as id -un. --help display this help and exit --version output version information and exit Report bugs to sh-utils-bugs@gnu.ai.mit.edu $

This command outputs some usage information about the whoami

tool, including a short description and a list of possible options.

NOTE: Not all tools take the `--help' option; some tools take a `-h' or `-?' option instead, which performs the same function.

In the olden days, the hardcopy reference manual that came with most Unix systems also existed electronically on the system itself; each software program that came with the system had its own manual page (often called a "man page") that described it. This is still true on Linux-based systems today, except they don't always come with a hardcopy manual.

Use the man tool to view a page in the system manual. As an

argument to man, give the name of the program whose manual page

you want to view (so to view the manual page for man, you would

type man man).

w, type:

$ man w [RET]

This command displays the manual page for w:

Use the up and down arrow keys to move through the text. Press [Q]

to stop viewing the manual page and exit man. Since man

uses less to display the text, you can use any of the less

keyboard commands to peruse the manual page (see Perusing Text).

Despite its name, a manual page does not always contain the complete documentation to a program, but it's more like a quick reference. It usually gives a short description of the program, and lists the options and arguments it takes; some manual pages also include an example or a list of related commands. (Sometimes, commands have very complete, extensive manual pages, but more often, their complete documentation is found either in other help files that come with it or in its Info documentation; these are subjects of the following two recipes.)

To prepare a man page for printing, see Preparing a Man Page for Printing.

The GNU Info System is an online hypertext reference system for

documentation prepared in the Info format. This documentation tends to

be more complete than a typical man page, and often, the Info

documentation for a given software package will be an entire book or

manual. All of the manuals published by the Free Software Foundation are

released in Info format; these manuals contain the same text

(sans illustrations) as the paper manuals that you can purchase

directly from the Free Software Foundation.

There are different ways to peruse the Info documentation: you can use

the standalone info tool, read Info files in the Emacs editor

(see Emacs), or use one of the other tools designed for

this purpose. Additionally, tools exist for converting Info

documentation to HTML that you can read in a Web browser

(see Browsing Files).

To read the Info manual for a tool or application with the info

tool, give its name as an argument. With no arguments, info opens

your system's Top Info menu, which lists all of the available

manuals that are installed on the system.

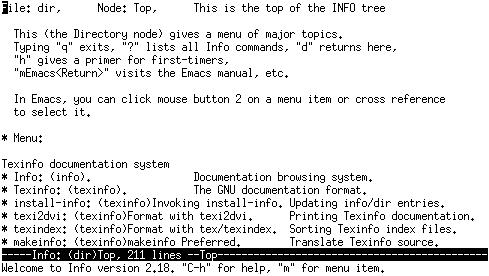

$ info [RET]

This command starts info at the system's Top menu, which

shows some of the info key commands and displays a list of

available manuals:

Use the arrow keys to move through each "page" of information, called

an Info node. Nodes are the base unit of information in Info, and

are arranged hierarchically -- a manual's Top node will contain an

Info menu containing links to its various chapters, and a chapter

node will contain a menu with links for its sections, and so on. Links

also appear as cross references in the text.

Links look the same in both menu items and cross references: an asterisk (`*'), the name of the node it links to, and either one or two colon characters (`:'). To follow a link to the node it points to, move the cursor over any part of the node name in the link and press [RET].

To run a tutorial that describes how to use info, press the

[H] key. Press [Q] at any time to stop reading the documentation

and exit info.

To read Info documentation for a tool or application, give its name as

an argument to info; if no Info manual exists for that tool,

info displays the man page for that tool instead.

tar tool, type:

$ info tar [RET]

This command opens a copy of The GNU tar Manual in info.

To read the contents of a file written in Info format, give the name of the file to read with the `-f' option. This is useful for reading an Info file that you have obtained elsewhere, and is not in the `/usr/info' directory with the rest of the installed Info files. Info can automatically recognize and expand Info files that are compressed and have a `.gz' file name extension (see Compressed Files).

$ info -f faq.info [RET]

This command starts info and opens the Info file `faq.info',

beginning at the top node in the file.

To read a specific node in an Info file, give the name of the node to use in quotes as an argument to the `-n' option.

Text, type:

$ info -n 'Text' -f faq.info [RET]

NOTE: You can also read Info documentation directly from the

Emacs editor; you type C-h i from Emacs to start the Info reader,

and then use the same commands as in the standalone info tool

(see Getting Acquainted with Emacs).

The Emacs "incremental" search command, C-s, also works in

info; it's a very fast, efficient way to search for a word or

phrase in an entire Info text (like this entire book); see Searching Incrementally in Emacs.

Debian: `doc-linux-text' WWW: http://linuxdoc.org/

The `/usr/doc' directory is for miscellaneous documentation:

HOWTOs, FAQs, Debian-specific documentation files and documentation

files that come with commands. (To learn more about files and

directories, see Files and Directories.)

To peruse any of these files, use less, described in full in

Perusing Text.

When a software package is installed, any additional documentation files

it might have beyond a manual page and Info manual are placed here, in a

subdirectory with the name of that package. For example, additional

documentation for the hostname package is in

`/usr/doc/hostname', and documentation for the passwd

package is in `/usr/doc/passwd'. Most packages have a file called

`README', which usually contains relevant information. Often this

file is compressed as `README.gz', in which case you can use

zless instead of less.

The Linux Documentation Project (LDP) has overseen the creation of more than 100 "HOWTO" files, each of which covers a particular aspect of the installation or use of Linux-based systems.

The LDP HOWTOs are compressed text files stored in the

`/usr/doc/HOWTO' directory; to view them, use zless. The

file `/usr/doc/HOWTO/HOWTO-Index.gz' contains an annotated index of

all the HOWTO documents installed on the system.(11)

Finally, the `/usr/doc/FAQ' directory contains a number of FAQ

("Frequently Asked Questions") files on various subjects, and the

files that make up the Debian FAQ are in the `/usr/doc/debian/FAQ'

directory. The Debian FAQ is available both in HTML format, which you

can view in a Web browser (see Browsing Files),

and as a compressed text file, which you can view in zless.

lynx Web

browser, type:

$ lynx /usr/doc/debian/FAQ/debian-faq.html [RET]

zless,

type:

$ zless /usr/doc/debian/FAQ/debian-faq.txt.gz [RET]

NOTE: It's often very useful to use a Web browser to browse through the documentation files in these directories -- see Browsing Files.

On some systems, `/usr/doc' is superseded by the `/usr/share/doc' directory.

[<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->]