| [<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->] |

There are many Internet services other than email and the World Wide

Web; this chapter describes how to use many of the other popular

services, including telnet, ftp, and finger.

Use telnet to connect to a remote system. Give the name of the

system to connect to as an argument, specifying either its name or

numeric IP address. If that system is reachable, you will be connected

to it and presented with a login: or other connection prompt (the

network is not exclusive to Linux systems) just as if you were seated at

a terminal connected to that system. If you have an account on that

system, you can then log in to it (see Logging In to the System).

kanga.ins.cwru.edu, type:

$ telnet kanga.ins.cwru.edu [RET]

Trying 129.22.8.32...

Connected to kanga.INS.CWRU.Edu.

Escape character is '^]'.

BSDI BSD/OS 2.1 (kanga) (ttypf)

/\

WELCOME TO THE... _! !_

_!__ __!_

__ ! !

_! !_ ! ! ! !

! ! /\ ! ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! !___

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !

! !_!_ ! ! ! ! ! !

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !

_! ! !_!_ ! ! !_

! ! !_! ! !

! !

! CLEVELAND FREE-NET !

! COMMUNITY COMPUTER SYSTEM !

!____________________________________!

brought to you by

Case Western Reserve University

Office of Information Services

Are you:

1. A registered user

2. A visitor

Please enter 1 or 2: 1 [RET]

Enter your user ID (in lower case) at the Login: prompt.

Then enter your password when asked. Note that the

password will not print on the screen as you type it.

Login:

In this example, the user connected to the system at

kanga.ins.cwru.edu; the bottom Login: prompt was the

prompt of the remote system (if you are ever unsure what system you are

on, use hostname as a shell prompt; see Running a Command).

To disconnect from the system, follow the normal procedures for logging out from the system you are connected to (for how to do that on a Linux system, see Logging Out of the System).

$ C-d Connection closed. $

In the preceding example, the first shell prompt was on the remote system, and the second prompt was on the local system.

You can also temporarily escape back to the local shell by typing

the escape character, which is a key sequence that is interpreted

by telnet before it reaches the remote system. You will then be

brought to the telnet command prompt, where you can suspend with

the `z' command; to return to the remote system, bring the job back

into the foreground (see Putting a Job in the Foreground).

faraway-system$ C-[ telnet> z [RET] [2]+ Stopped telnet $

$ fg [RET] faraway-system$

In the first of the two preceding examples, the escape character

C-[ was typed on the remote system, whose shell prompt in this

example is `faraway-system$' (you don't have to type the escape

character at a shell prompt, though; you can type it regardless of what

program you are running or where you are on the remote system). Then,

the `z' command was given to telnet to suspend the

telnet connection. In the second example, the suspended

telnet connection to the remote system was brought back into the

foreground.

NOTE: You should be aware that it's possible (though not often

desirable) to "nest" multiple layers of telnet sessions on top

of each other by connecting from one system to the next, to the next,

and so on, without disconnecting from the previous system. To avoid

this, make sure you know which host you're leaving when you're about to

telnet off to another; the hostname tool is useful for

this (see Logging In to the System).

Debian: `kerberos4kth-user' WWW: http://web.mit.edu/kerberos/www/ WWW: http://www.openssh.com/

On some systems, your system administrator may ask you to install and

use kerberos, openssh, or some other network security tool

so that you may connect to a remote system in a more secure manner than

with telnet. These tools encrypt the data that is passed between

the local and remote systems during your connect session; they're

becoming very popular today among security-conscious

administrators. Should you be asked to use one, follow your

administrator's instructions in installing and configuring it for your

system.

NOTE: In order to be of any use, the services and tools discussed in this chapter require that your system is online or otherwise connected to a network; see Communications.

FTP ("File Transfer Protocol") is a way to exchange files across

systems. Use the ftp tool to connect to another system using this

protocol, giving the name or numeric IP address of the system you want

to connect to as an argument. Once connected, you will be prompted to log

in with a username and password (if you have one on that system).

Many systems are set up to accept "anonymous ftp" connections, where a

public repository of files are available for downloading by the general

public; to use this, log in with a username of anonymous, and

give your email address for a password.

ftp connection to ftp.leo.org,

type:

$ ftp ftp.leo.org [RET] Connected to ftp.leo.org. 220-Welcome to LEO.ORG. 220-See file README for more information about this archive. 220- 220-Your connection class is named: The world outside Germany 220- 220-If you don't connect from inside Munich and login anonymously, 220-your data transfers are limited to a certain bandwidth. 220- 220-If you notice unusual behaviour, drop a note to ftp-admin@leo.org. 220 FTP server leo.org-0.9alpha ready. Name (ftp.leo.org:m): anonymous [RET] 331 Guest login ok, send your email address as password. Password: at118@po.cwru.edu [RET] 230- _ ___ ___ 230- | | | __|/ \ LEO - Link Everything Online 230- | |__| _| | - | Munich University of Technology (TUM) 230- |___/|___|\___/ Department of Computer Science 230- 230- This Anonymous FTP site is in Munich, Germany, Europe. 230- It's Tue Sep 28 18:31:43 MET DST 1999. 230- Please transfer files during non-business hours (1800-0900 CET). Remote system type is UNIX. Using binary mode to transfer files. ftp>

Once connected and logged in, use the cd and ls commands

to change directory and to list files on the remote system.

It is standard practice for public systems to have a `/pub' directory on their FTP host that contains all the files and goodies available to the general public.

ftp> cd /pub [RET] 250 Directory changed to /pub. ftp> ls [RET] ftp> ls 200 PORT command successful. 150 Opening ASCII connection for file (918 bytes) total 30258 -rw-rw-r-- 1 ftpadmin ftpadmin 10942767 Sep 28 06:18 INDEX.gz drwxr-xr-x 5 ftpadmin ftpadmin 512 Sep 17 18:22 comp -rw-rw-r-- 1 ftpadmin ftpadmin 9512498 Sep 28 06:40 ls-lR.gz drwxr-xr-x 2 ftpadmin ftpadmin 512 Sep 17 18:22 rec drwxr-xr-x 3 ftpadmin ftpadmin 512 Sep 17 18:22 science 226 Transfer completed with 918 Bytes/s. ftp>

In this example, the `/pub' directory contained three

subdirectories (`comp', `rec', and `science') and two

files, `INDEX.gz' and `ls-lR.gz'; many public systems have

files similar to these in their `/pub'

directories---`INDEX.gz' is a listing of all files on their

ftp site, with descriptions, and `ls-lR.gz' is the output of

the command ls -lR run on the directory tree of their ftp

server.

The following subsections describe how to upload and download files.

Use the quit command to exit ftp and end the connection to

the remote system.

Use the put command to upload a file; give the name of the file

as an argument. put takes that file in the current directory of

the local system, and puts a copy of it in the current directory of the

remote system.

ftp> put thyme.rcp [RET]

The current directory of the local system is, by default, the

directory where you ran the ftp command. To change directories on

your local system, use lcd; it works just like the cd

command, but it changes the local directory.

ftp> lcd .. [RET] Local directory now /home/james/demos ftp>

In this example, the local current directory is now `/home/james/demos'.

There are other important commands for downloading files -- use `i' to specify that files be transferred as binary; normally, the transfer is set up for text files. When you want to transfer programs, archives, compressed files, or any other non-text file, set the transfer type to `i' first.

In recent years, most public systems have added a security measure forbidding the upload by anonymous users to anywhere but the `/incoming' or `/pub/incoming' directories.

The mput command works like put but allows you to specify

wildcards. By default, mput asks you, for each file, whether to

upload the file or not; to turn off this file prompting, type

prompt before giving the mput command. This command is a

toggle -- type prompt again to turn file prompting back on for your

session.

The get command works like put, but in reverse -- specify a

file on the remote system, and get saves a copy to the current

directory on the local system. Again, use i first when downloading

non-text files. (You can also download text files with i, so it is

good practice to always set it before you transfer files; most

Linux systems are configured to set the type to `i' immediately

upon connection).

ftp> lcd ~/tmp [RET] Local directory now /home/james/tmp ftp get INDEX.gz [RET] local: INDEX.gz remote: INDEX.gz Transferred 10942767 bytes ftp>

NOTE: The mget command works like get but allows

wildcards; as with mput, you will be prompted to verify each file

unless you use the prompt command first to turn this off.

WWW: http://www.faqs.org/usenet/index.html WWW: http://www.geocities.com/ResearchTriangle/Lab/6882/

Usenet is a famous, vast collection of world-around discussion boards

called newsgroups, where messages (called articles) can be

read and publicly responded to. Newsgroups are named and organized by

hierarchy, with each branch delineated by a period (`.'); for

example, the `comp.os.linux' newsgroup is part of the

`comp.os' branch of the `comp' hierarchy.

The following table lists the "Big Eight" Usenet hierarchies and give examples of some newsgroups in each one.

| USENET HIERARCHY | DESCRIPTION |

comp |

Computing. news:comp.os.linux.advocacy, news:comp.text.tex |

humanities |

Humanities. news:humanities.music.composers.wagner |

misc |

Miscellaneous. news:misc.consumers.frugal-living |

news |

Newsgroups relating to Usenet

itself. news.newusers.questions |

rec |

Recreation. news:rec.music.marketplace.vinyl, news:rec.food.cooking |

sci |

Science. news:sci.math, news:sci.cognitive |

soc |

Social groups and cultures. news:soc.culture.usa, news:soc.college |

talk |

Talk and chit-chat. news:talk.environment, news:talk.politics.guns |

An application that lets you read and post articles to newsgroups is called a newsreader. Here are some of the best newsreaders available for Linux-based systems.

| NEWSREADER | DESCRIPTION |

gnus |

Gnus is a very powerful and feature-full newsreader for use in

Emacs. You can use it to read mail, too.

Debian: `gnus' WWW: http://www.gnus.org/ |

knews |

A graphical newsreader for use in X. Its features include the

display of article threads in a graphical tree, and options for those

reading news over slow connections.

Debian: `knews' WWW: http://www.matematik.su.se/~kjj/ |

mozilla |

Historically, commercial Web browsers also had mail and newsreaders

built into them, and that capability remains in the Mozilla browser.

Debian: `mozilla' WWW: http://www.mozilla.org/ |

nn |

The motto of nn is "No News is good news, but nn is

better"; it's an older (and very popular) newsreader that was designed

for reading the most news in the minimal amount of time.

Debian: `nn' WWW: http://www.math.fu-berlin.de/~guckes/nn/ |

pan |

The "Pimp A** Newsreader" is a new-generation graphical

newsreader that is designed for speed. It is meant to be easy for

beginners to use, and it works in X with GNOME installed.

Debian: `pan' WWW: http://www.superpimp.org/ |

peruser |

News Peruser is a suite of small tools for use in X that

facilitate the reading and composing of news articles when you're

offline -- it downloads batches of news when your system is online.

Debian: `peruser' WWW: http://www.ibiblio.org/pub/Linux/system/news/readers/ |

slrn |

Based on rn, one of the oldest newsreaders, slrn is

optimized for use over slow connections (like home modem dial-ups).

Debian: `slrn' WWW: http://www.slrn.org/ |

Debian: `nn' WWW: ftp://ftp.uwa.edu.au/pub/nn/beta/

Use nngrep to find newsgroup names that match a pattern. This is

useful for finding groups on a particular topic.

$ nngrep society [RET]

Use the `-u' option to only search through unsubscribed groups. This is useful if you are subscribed to a number of groups, and you are looking only for groups you aren't subscribed to yet.

$ nngrep society [RET]

In the previous example, if you were already subscribed to the group

alt.society.neutopia, that group will not be displayed; but other

groups matching the pattern `society' that you are not subscribed

to would be listed.

The following tools are used to list the activity of other users and systems on the Internet -- showing whether or not they are currently online and perhaps displaying a little more information about them.

Use ping to determine whether a particular system is currently

connected to the Internet.

Type ping followed by the name or numeric IP address of the system

you want to check; if your system is online and the system to be checked

is also online, ping should continually output lines telling how

long the latency, in milliseconds, is between the two systems. Type

C-c to interrupt it and stop pinging.

bfi.org, type:

$ ping bfi.org [RET] PING bfi.org (209.196.135.250): 56 data bytes 64 bytes from 209.196.135.250: icmp_seq=0 ttl=63 time=190.0 ms 64 bytes from 209.196.135.250: icmp_seq=1 ttl=63 time=159.9 ms 64 bytes from 209.196.135.250: icmp_seq=2 ttl=63 time=160.5 ms C-c --- bfi.org ping statistics --- 3 packets transmitted, 3 packets received, 0% packet loss round-trip min/avg/max = 159.9/170.1/190.0 ms $

In this example, the host bfi.org was pinged and a total

of three pings were sent and received before the user typed

C-c to interrupt it. As long as these ping lines are

output, you know that the other machine is connected to the Internet (or

at least to the same network that your localhost is connected to).

You really don't need to analyze the information on each line of a

ping message -- the only useful information is the number at the

end of the line, which tells you how many milliseconds it took to go out

to the Internet, touch or "ping" that host, and come

back.(43) The quicker the better---pings that are four or five

digits long (or greater) mean a slow connection between the two

machines. When you interrupt the ping, some statistics are

output, including the minimum, average, and maximum number of

milliseconds it took to ping the given host. In the example

above, the high was 190 and the low was 159.9 milliseconds, with an

average of 170.1.

NOTE: If your own system is not online, ping will report

that either the network is unreachable or that the host isn't found.

Use finger to check whether or not a given user is online. Give

as an argument the username of the user (if on the local system) or

their email address (if on a remote system). This is called

"fingering" a user.

If the system they are using has finger enabled (most Unix-based

systems should), the command will tell you the following: the date and

time when they last logged in; whether or not they are currently logged

in; their full name; their office room and telephone number; their home

directory; what shell they use; whether or not they have mail waiting;

the last time they read mail; and, finally, their "plan," as described

below.

jsmith@ap.example.org, type:

$ finger jsmith@ap.example.org [RET] [ap.example.org] Login: jsmith Name: James Smith Directory: /sp1/jsmith Shell: /bin/tcsh Last login Wed Jan 20 16:38 1999 (PST) on ttypb from zais.example.com No mail. Plan: To learn to how use Linux and GNU software. $

In this example, the user jsmith on the system at

ap.example.org is not currently logged in, logged in last

on 20 January, and uses the tsch shell.

NOTE: On Unix-based systems, you can put information in a

hidden file in your home directory called `.plan', and that text

will be output when someone fingers you. Some people put

elaborate information in their `.plan' files; in the early 1990s,

it was very much in vogue to have long, rambling

.plans. Sometimes, people put information in their `.plan'

file for special events -- for example, someone who is having a party

next weekend might put directions to their house in their `.plan'

file.

To get a listing of all users who are currently logged in to a

given system, use finger and specify the name (or numeric IP

address) of the system preceded with an at sign (`@').

This gives a listing of all the users who are currently logged in on that system. It doesn't give each individual's `.plan's, but the output includes how long each user has been idle, where they are connected from, and (sometimes) what command they are running. (The particular information that is output depends on the operating system and configuration of the remote system.)

ap.spl.org, type:

$ finger @ap.spl.org [RET] [spl.org] Login Name Tty Idle Login Time Office allison Allison Chaynes *q2 16:23 Sep 27 17:22 (gate1.grayline) gopherd Gopher Client *r4 1:01 Sep 28 08:29 (gopherd) johnnyzine Johnny McKenna *q9 15:07 Sep 27 16:02 (johnnyzine) jezebel Jezebel Cate *r1 14 Sep 28 08:42 (dialup-WY.uu.net) jsmith J Smith t2 2 Sep 28 09:35 (example.org) $

When you know the name of a particular host, and you want to find the IP

address that corresponds to it, ping the host in question; this

will output the IP address of the host in parenthesis (see Checking Whether a System Is Online).

You can also use dig, the "domain information groper" tool.

Give a hostname as an argument to output information about that host,

including its IP address in a section labelled `ANSWER SECTION'.

linart.net, type:

$ dig linart.net [RET] ...output messages... ;; ANSWER SECTION: linart.net. 1D IN A 64.240.156.195 ...output messages... $

In this example, dig output the IP address of

64.240.156.195 as the IP address for the host linart.net.

To find the host name for a given IP address, use dig with the

`-x' option. Give an IP address as an argument to output

information about that address, including its host name in a section

labelled `ANSWER SECTION'.

216.92.9.215, type:

$ dig -x 216.92.9.215 [RET] ...output messages... ;; ANSWER SECTION: 215.9.92.216.in-addr.arpa. 2H IN PTR rumored.com. ...output messages... $

In this example, dig output that the host name corresponding to

the given IP address was rumored.com.

An Internet domain name's domain record contains contact

information for the organization or individual that has registered that

domain. Use the whois command to view the domain records for the

common .com, .org, .net, and .edu top-level

domains.

With only a domain name as an argument, whois outputs the name of

the "Whois Server" that has that particular domain record. To output

the domain record, specify the Whois Server to use as an argument to the

`-h' option.

linart.net, type:

$ whois linart.net [RET]

linart.net, using the

whois.networksolutions.com Whois Server, type:

$ whois -h whois.networksolutions.com linart.net [RET]

NOTE: This command also outputs the names of the nameservers that handle the given domain -- this is useful to get an idea of where a particular Web site is hosted.

Use write to write a message to the terminal of another

user. Give the username you want to write to as an argument. This

command writes the message you give, preceded with a header line

indicating that the following is a message from you, and giving the

current system time. It also rings the bell on the user's terminal.

$ write sleepy [RET] Wake up! C-d $

The other user can reply to you by running write and giving your

username as an argument. Traditionally, users ended a write

message with `-o', which indicated that what they were saying was

"over" and that it was now the other person's turn to talk. When a

user believed that a conversation was completed, the user would end a

line with `oo', meaning that they were "over and out."

A similar command, wall, writes a text message to all other users

on the local system. It takes a text file as an argument and outputs the

contents of that file; with no argument, it outputs what you type until

you type C-d on a line by itself. It precedes the message with the

text `Broadcast message from username' (where username

is your username) followed by the current system time, and it rings the

bell on all terminals it broadcasts to.

$ wall /etc/motd [RET]

$ wall [RET] Who wants to go out for Chinese food? [RET] C-d

You can control write access to your terminal with mesg. It works

like biff (see Setting Notification for New Mail):

with no arguments, it outputs whether or not it is set; with `y' as

an argument, it allows messages to be sent to your terminal; and with

`n' as an argument, is disallows them.

The default for all users is to allow messages to be written to their terminals; antisocial people usually put the line mesg n in their `.bashrc' file (see Customizing Future Shells).

$ mesg n [RET]

$ mesg [RET] is n $

In the preceding example above, mesg indicated that messages are

currently disallowed to be written to your terminal.

There are several ways to interactively chat with other users on the Internet, regardless of their platform or operating system. The following recipes describe the most popular tools and methods for doing this.

Debian: `ytalk' WWW: http://www.iagora.com/~espel/ytalk/

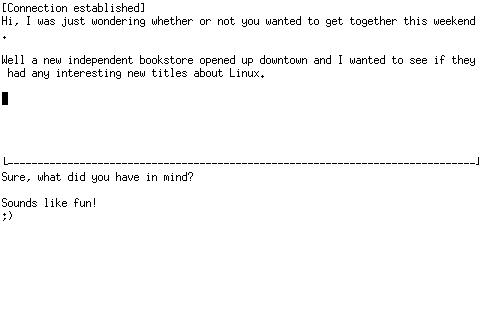

Use talk to interactively chat in realtime with another

user. Give the username (or email address) of the user you want to chat

with as an argument; a message will be sent to that user's terminal,

indicating that a connection is requested. If that person then runs

talk, giving your username as an argument, you will both be

connected in a talk session -- the screen will clear and then what

you type will appear on the top of the screen; what the other user types

will appear at the bottom of the screen.

kat@kent.edu, type:

$ talk kat@kent.edu [RET]

This command sends a connection request to the user

kat@kent.edu. If the user is not logged on or is refusing

messages, talk will output a message indicating such; but if that

user is available, talk will send a message to that user asking

to complete the connection, and it will tell you that it is ringing your

party.

If that user then types talk stutz@dsl.org (if, in this example,

your email address is stutz@dsl.org), then your screen will

clear and you will see the following:

You can then type, and what you type will appear on both your screen and that user's screen; that user, in turn, can also type -- even while you are typing -- and what that user types appears on the other half of both screens:

It is standard practice to indicate that you are done saying something by typing [RET] [RET], thus making a blank line on your half of the screen. Some users, when they have typed to the bottom of their half of the screen, sometimes type [RET] repeatedly to "clear" their half of the screen and bring the cursor back to the top.

Type C-c to end a talk session.

When you type, both users see the characters appear in realtime; my first demonstration of the interactive nature of the Internet, back in 1991, was when I had a live, real-time chat with a user in Australia, on the other side of the globe -- the magic felt that day has never quite left whenever I run this command!

NOTE: A similar command, ytalk, allows you to connect to

multiple users, and it contains other features as well; it is generally

considered to be the superior successor of talk, but it is not

yet available or standard on all Unix-based systems.

Internet Relay Chat (IRC) is a global chat system, probably the oldest and largest on the Internet. IRC is a great way to meet and talk to all kinds of people, live on the Internet; it has historically been very popular with Linux users.

There are several IRC networks, each with its own servers and tens of thousands of users; to "go on" IRC, you use an IRC client program to connect with an IRC server. Like CB radio, IRC networks have channels, usually based on a particular topic, which you join to chat with other users in that channel (you can also send private messages to other users).

The following table lists some of the IRC clients available for Linux.

| CLIENT | DESCRIPTION |

bitchx |

BitchX is an IRC client whose features include ANSI color, so it

can display all of the character escape codes that are popularly used on

IRC for special effects. Despite what you might gather from its name, it

doesn't require X in order to run.

Debian: `bitchx' WWW: http://www.bitchx.org/ |

epic |

EPIC is a large, feature-filled IRC client.

Debian: `epic' WWW: http://www.epicsol.org/ |

irssi |

A modular IRC client; note that some versions can only be run in X

with GNOME.

Debian: `irssi' WWW: http://irssi.org/ |

xchat |

Xchat is a graphical IRC chat client for use in X.

Debian: `xchat' WWW: http://www.xchat.org/ |

zenirc |

ZenIRC is a minimalist, no-frills (yet fully extensible) IRC mode

for Emacs.

Debian: `zenirc' WWW: http://www.splode.com/~friedman/software/emacs-lisp/zenirc/ |

WWW: http://www.portup.com/~gyandl/icq/

In the late 1990s, a company called Mirabilis released a proprietary

program for PCs called ICQ ("I Seek You"), which was used to send text

messages to other users in realtime. Since then, many free software

chat tools have been written that use the ICQ protocol.

One nice feature of ICQ is is that you can maintain a "buddy list" of

email addresses, and when you have an ICQ client running, it will tell

you whether or not any of your buddies are online. But unlike

talk, you can't watch the other user type in realtime -- messages

are displayed in the other user's ICQ client only when you send them.

The following table lists some of the free software ICQ clients currently available.

| CLIENT | DESCRIPTION |

licq |

Licq is an ICQ client for use in X.

Debian: `licq' WWW: http://www.licq.org/ |

micq |

Micq ("Matt's ICQ clone") is an easy-to-use ICQ client that can

be used in a shell.

Debian: `micq' WWW: http://phantom.iquest.net/micq/ |

zicq |

Zicq is a version of Micq with a modified user interface.

Debian: `zicq' |

[<--] [Cover] [Table of Contents] [Concept Index] [Program Index] [-->]